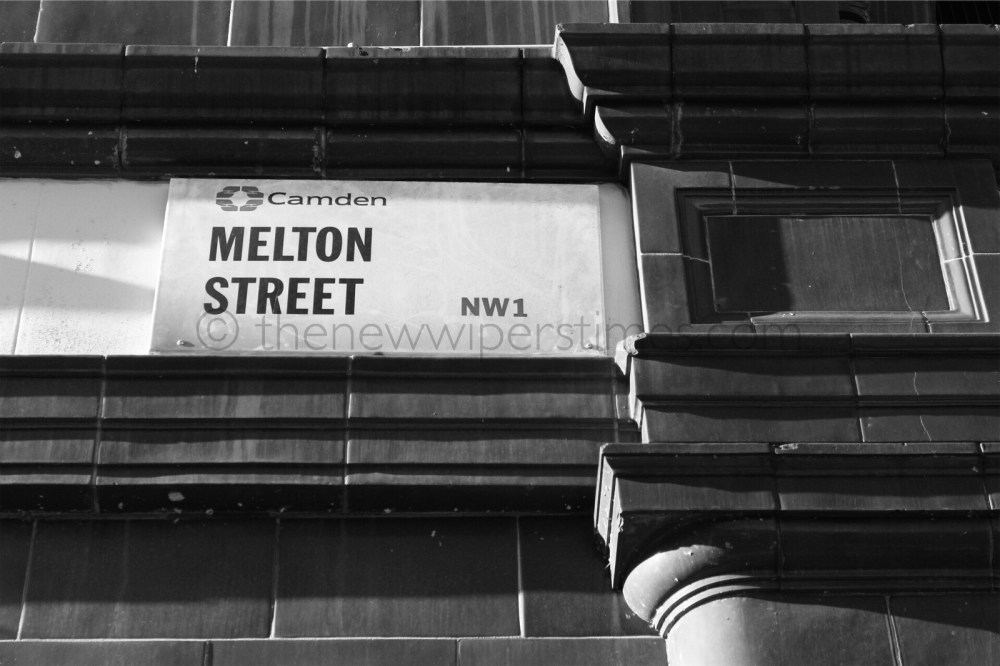

I have always been fascinated with London’s abandoned Tube stations, so when an email from London Transport Museum dropped in to my inbox on 21 November 2017 for Euston – The Photography Tour, as part of their Hidden London programme, I duly paid my £100 for a ticket and signed up. At 10:45 on 7th February, 2018, I was standing at 16, Melton Street, N.W.1, DSLR in hand, waiting for the tour to begin.

For anyone with even a passing interest in the design of London Underground, there are two architects that stand out, above all others; Leslie Green (1875-1908); and Charles Holden (1875-1960). Between them, the pair designed some of the most important stations on the network, many of which still stand today.

Whilst Holden is best remembered for his work on the Piccadilly line extensions of the 1930’s, and London Underground’s very own Grade I-listed headquarters at 55 Broadway, S.W.1, Green’s legacy remains the core stations on what we now know as the Bakerloo, Northern and Piccadilly lines. Euston is one such station.

Standing at the junction of Melton Street and Drummond Street, Euston was built as one of 16 original stations on the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR), which was formally opened at precisely 13:30 on Saturday 22nd June, 1907, by David Lloyd-George, M.P.

The deep-level, underground railway ran from Charing Cross station in the south to Golders Green and Highgate (now Archway) in the north, with the eight mile line separating in to two branches at Camden Town.

The ‘Hampstead Tube‘ as it was known, was one of three entirely new underground lines to open in London during the first decade of the 20th Century – the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (BS&WR), the CCE&HR, and the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (GNP&BR) – showing the sheer ambition of both the era, and the American financier, Charles Tyson Yerkes, Chairman of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London Limited (UERL), who developed them.

Appointed as Architect by Yerkes, Green would end up designing more than 50 Tube station buildings for the UERL. Whilst no two stations were the same in terms of their footprint or as a result, their exterior, they all shared many common design elements in the same way that the Jubilee Line Extension stations do today.

Each building was constructed around a structural steel frame, which allowed them to be erected both quickly and cheaply, whilst also offering the potentially lucrative opportunity for over-station buildings, as occurred at Tottenham Court Road (now Goodge Street) among others.

With its distinctive facade of highly-glazed ox-blood red terracotta blocks, supplied by the Leeds Fireclay Company, Euston is a classic example of Green’s work, which drew upon the Arts and Craft style.

© TfL from the London Transport Museum collection

© TfL from the London Transport Museum collectionExteriors were based around a series of repeating pillars and arches, which created a uniform appearance across the three lines, regardless of the buildings width. Whilst Euston, for example, features five arches along its two sides, Chalk Farm station features no less than 14.

Each arch was complimented by a semi-circular window within, which sat atop a horizontal band of white tiles that ran the entire width of the station and separated the ground and first storey, whilst also displaying the station name.

Smaller widths, to accommodate access doors or windows at ground floor level, made use of either small circular porthole windows, or large rectangular windows on the upper level. For exterior lighting, Maxim arc lamps were suspended from elaborate wrought iron frames.

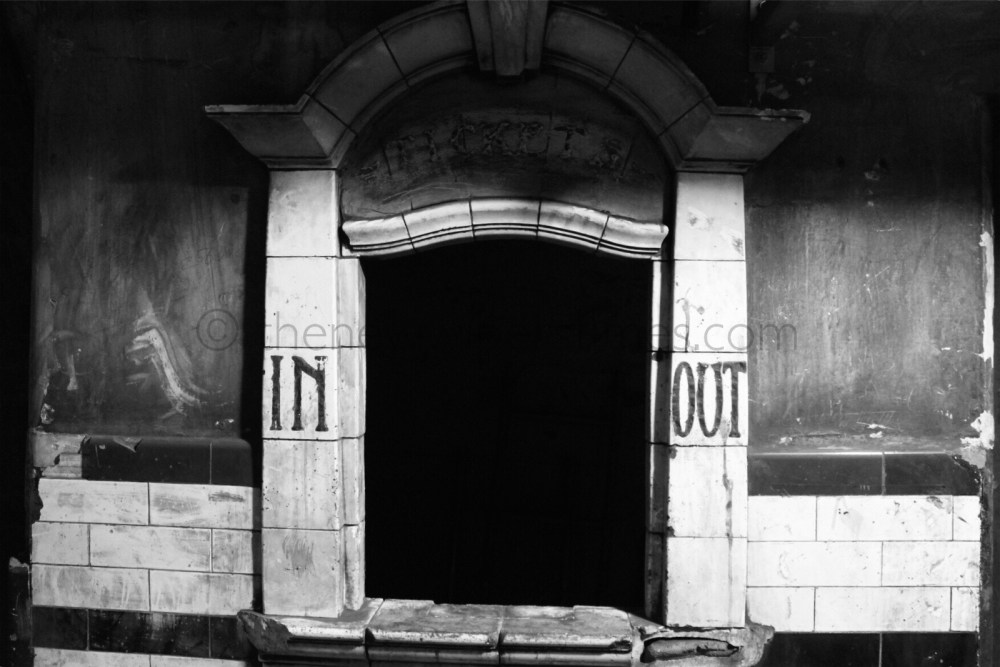

Passengers would enter the booking hall at Euston via the Drummond Street frontage, with Melton Street strictly ‘Exit Only’. In contrast to the exterior, the ticket halls were finished with deep green decorative tiles.

The station was originally built with two pairs of lifts, supplied by the Otis Elevator Company, which would have been situated on the left-hand side of the booking hall when entering the station, along with a spiral staircase straight ahead, all of which descended to a low-level landing area.

Once out of the lifts, passengers would turn left and follow a one-way system down a flight of stairs, which brought them out at the southern end of the Northbound platform (Platform 1 today). To exit the station, a separate passageway led from the southern end of the Southbound platform (Platform 2 today) back to the lifts.

As with other stations across the UERL lines, the platforms were elaborately tiled with glazed blue and white faience tiles, in a geometric pattern unique to Euston. The passageways were tiled in the same style.

Having met at Melton Street, I had assumed that it would be these very passageways that we would be exploring, however that was not to be the case…

You see, on Saturday 11th May, 1907, just six weeks before the CCE&HR opened, another deep-level Tube line had already arrived at Euston – the City & South London Railway (C&SLR) – which had been extended north from Angel, with an intermediate station at King’s Cross and Euston as the northern terminus.

The C&SLR had its own separate surface building, which stood at the junction of Seymour Street (now Eversholt Street) and Doric Way, and was designed by the architect, Sidney R. J. Smith. The station featured a single pair of lifts and a staircase, which took passengers down to the western end of what was an island platform, similar to those still seen at Clapham North and Clapham Common today.

© TfL from the London Transport Museum collection

© TfL from the London Transport Museum collectionThe land on which the two competing station buildings sat was owned by the London & North Western Railway (L&NWR) who insisted that both companies commit to building a third entrance to their new lines on the mainline concourse. Situated beneath platforms 2 and 3 as they were in the old Euston station, the L&NWR booking hall, which was reached by two flights of stairs, was served by two lifts.

The lifts brought passengers down to another low-level landing area, from which they could reach either the CCE&HR or C&SLR platforms. One passageway led to the northern end of the Northbound CCE&HR platform – the landing level was below the platform level here, so passengers were tasked with ascending two flights of stairs.

The second passageway led down to the western end of the C&SLR island platform.

Finally, there was also a third passageway, which directly connected the two lines, and led from the western end of the C&SLR platforms to the northern end of the southbound CCE&HR platform (Platform 2 today). Unique to the Underground network, this passageway featured a subterranean booking office for passengers transferring between the two lines.

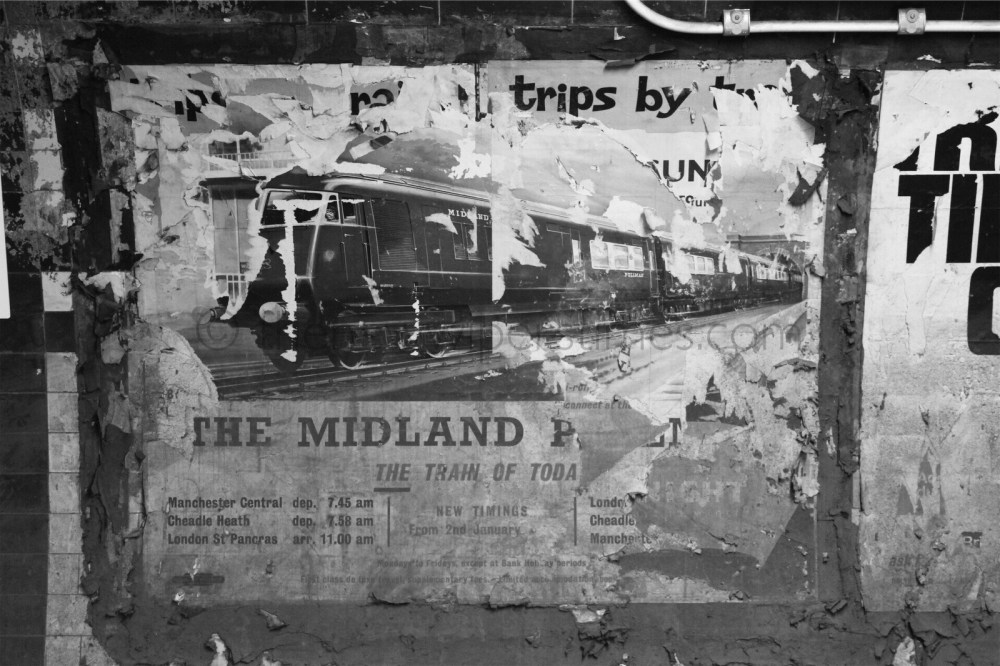

Perhaps unsurprisingly, and similar to today, most of the passengers at Euston were simply using the station as a means to transfer between the Underground lines and the mainline L&NWR stations, which meant that with direct platform access, it was the railway company’s own booking office and lifts that proved to be most popular. As a result, both the C&SLR and CCE&HR station buildings at Euston finally closed to passengers on 30th November, 1914.

The photo below, taken in 1914, as evidenced by Charles Pears’ poster, ‘Up River’, which can be seen on the corner of the station, shows that in the seven years since it opened, the surface building had already lost its exit on Melton Street, which was boarded up by means of corrugated metal sheets, with the primary entrance/exit now that of Drummond Street, where an early ‘Underground’ sign had been installed above the entrance, in front of the semi-circular window.

© TfL from the London Transport Museum collection

© TfL from the London Transport Museum collectionThe C&SLR station survived until the early 1930’s, when it was knocked down and replaced by Euston House, which was opened on February 12th, 1934 as the head office of the London Midland and Scottish (LMS) Railway, by Oliver Stanley, Minister of Transport.

The various subterranean passageways and mainline ticket office existed largely as-built for almost another 50 years before widespread reconstruction at Euston saw their abandonment. On 13th December, 1961, work commenced on the redevelopment of Euston underground station, which by that time was handling almost 11m people a year, and reliant on just three lift shafts, dating from the Edwardian era.

The plan at Euston was to therefore do away with the existing layout and infrastructure and build an entirely new station around the existing platforms, with the exception of the northbound C&SLR, which was to be diverted. A new sub-surface booking hall was planned, with four banks of twin escalators, leading to two intermediate lower-concourse levels, and providing full interchange with the Victoria line, for which plans had existed since 1949, yet sign off had not been given.

In order to allow the station to stay open throughout the works, the redevelopment was split in to two distinct phases, the first of which would see part of the new booking hall opened, a single bank of escalators and passageways for the Charing Cross branch.

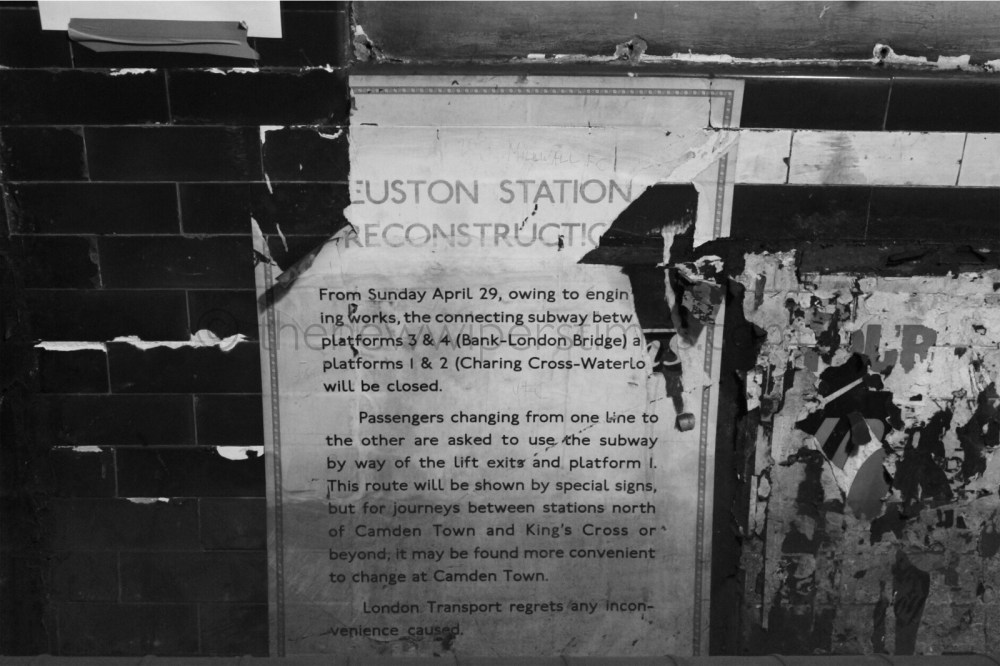

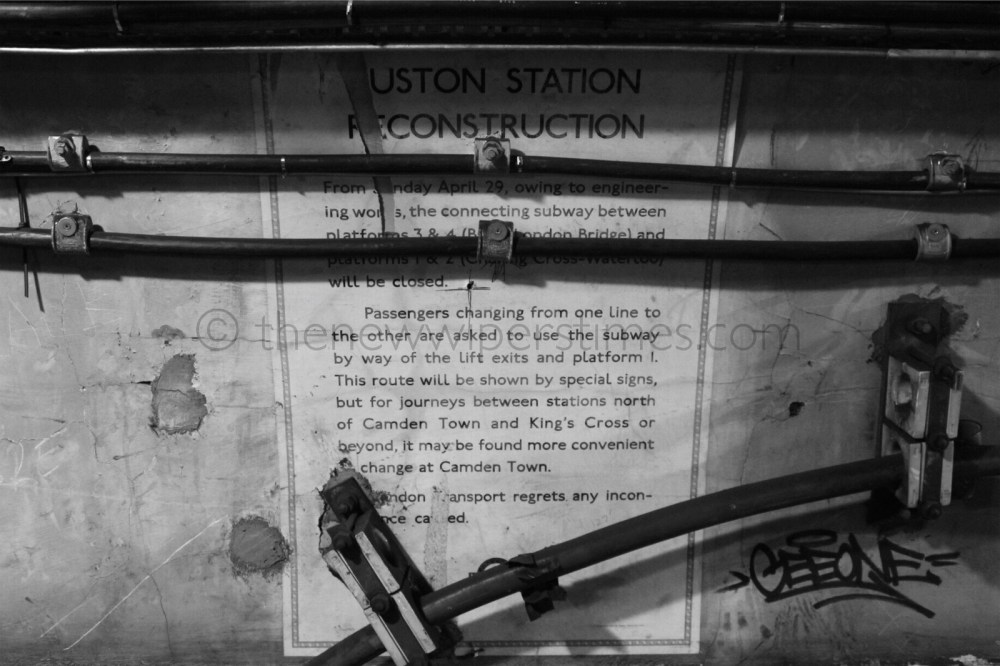

As such, on 29th April, 1962, the direct connection between the former CCE&HR and C&SLR lines was closed ‘owing to engineering works’. Later that year, on 20th August, the Victoria line was finally given sign-off by Ernest Marples, Minister of Transport.

Less than three years later, on 8 March, 1965, the first phase of works were completed and the new entrance and ticket hall opened. At this point, the two remaining passageways that took passengers from both branches of the Northern line to the mainline lifts closed to the public, alongside the lifts themselves. The final three escalator banks were brought in to use on 15th October, 1967.

A year later, on 14th October, the Queen formally opened the new Euston station, with the first Victoria line train stopping at the station on 1 December, 1968, having run from Warren Street in the south to Walthamstow in the north. V-Day, or 7th March, 1969 was when the Queen opened the new line in its entirety.

Throughout all of this, the CCE&HR surface building survived, despite losing almost its entire interior, with the booking hall, ticket office and lifts being removed to accommodate new ventilation systems, which also led to the loss of two of the semi-circular windows at the corner of the building.

Unsurprisingly, all of the station signage was removed, in order to avoid confusion, along with the wrought iron frames and attached lamps. All that remains of the original ticket hall is a small section of the deep green tiling, leading down to the spiral staircase, as seen in the photo below.

Sadly, and what I only found out right at the end of the tour is that at some point in 2018, the Leslie Green-designed surface building will finally be demolished.

When the High Speed Rail (London – West Midlands) hybrid Bill received Royal Assent on February 23rd, 2017, it inadvertently signalled the end for the station, as in order to accommodate 11 new HS2 platforms, Euston station’s existing footprint will extend both northwards and westwards, resulting in the demolition of 42 buildings and structures, including the disused entrance to Euston Underground Station on Melton Street.

February, 2018.

2 Comments Add yours